Arizona – like every state – levies taxes on the assessed value of all real property (land and its improvements), and on average, its overall property tax burden is relatively low. According to the Tax Foundation, Arizona collects $1,099 in real property taxes per person (ranking 34th) while the average state collects $1,167.

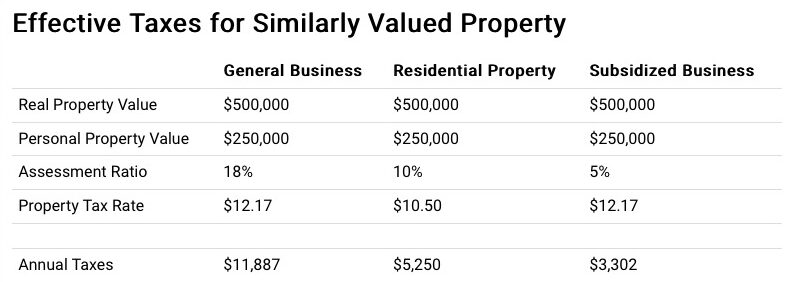

However, Arizona’s property tax burden falls disproportionately on certain payers: as a general example, a business with an assessed real property value of $500,000 might pay $11,887 a year in local property taxes, while an owner-occupied residence with the same value would pay $5,250.

Further, businesses are required to pay property taxes on the value of both real property (land and improvements) and personal property – the desks, computers, and other capital equipment that allow them to make productive use of their real property. Generally, personal property is between 20% and 50% of the value of underlying real property, and for certain capital-intensive businesses can be even higher. 11 states have no business personal property tax, and most states tax this property at lower rates than Arizona.

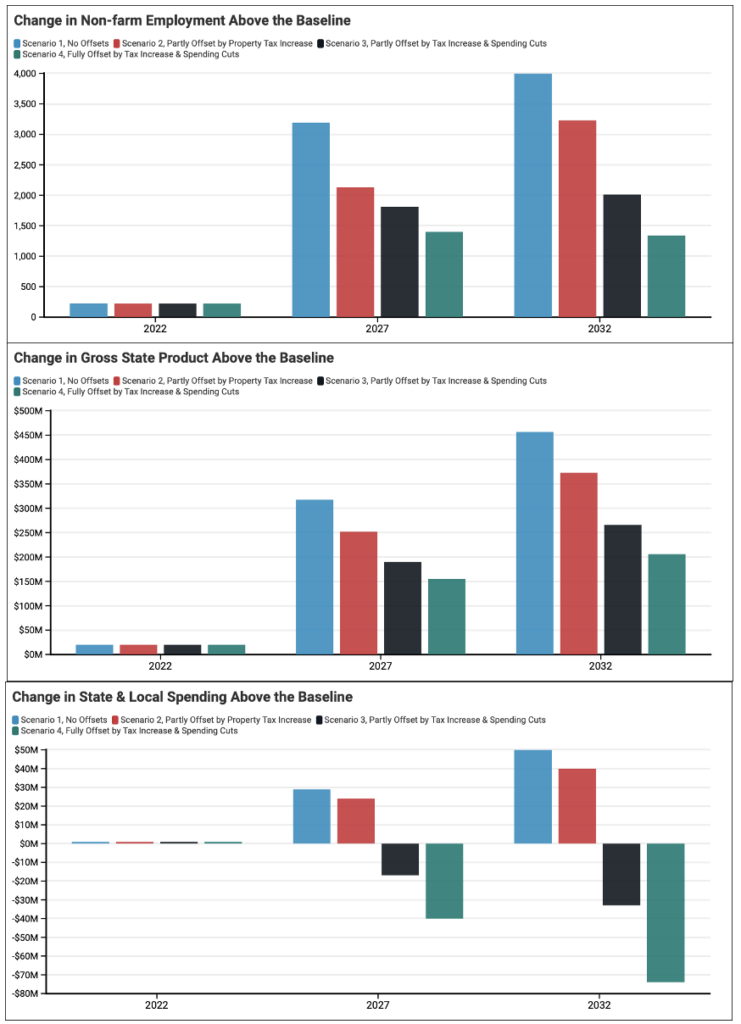

HB 2822 lowers and simplifies the tax burden on new capital investments by businesses in Arizona. In the process, the return-on-investment for a given asset rises, and the equilibrium level of investment will increase. To study the effects of this policy change on the Arizona economy, we used a dynamic economic simulation model to measure changes in investment, personal income, employment, and the costs of production and found that by 2032 this change results in:

- Approximately 3,000 more net jobs relative to current law, depending on the degree to which business capital cost savings are offset elsewhere by tax increases or government spending cuts.

- Between $204 million and $438 million in higher state personal income relative to current law.

- Between $263 million and $452 million higher Gross State Product relative to current law, including up to $264 million in new capital investment.

- After accounting for increased revenues on new economic activity, total state and government revenue could increase in 2032 by up to +$50 million on a dynamic basis, again depending on the degree of offset and relative to current law.

Overall, Common Sense Institute’s estimate of expected business capital tax savings (approximately $223 million in tax year 2032) results in net increases in private and total nonfarm employment and Gross State Product under all scenarios – including scenarios wherein taxpayer savings are fully offset by a combination of other property tax increases and state & local government spending reductions (an outcome we believe unlikely).

The high return on this policy is driven by its nature – the same amount of general property tax relief, for example, generates only between -543 and +2,035 jobs by 2032 relative to the baseline (depending on offset). This legislation combines the key principles of sound, efficient tax policy: broad-based relief that shifts the relative tax burden off investment and productive work and onto consumption of fixed assets like land.

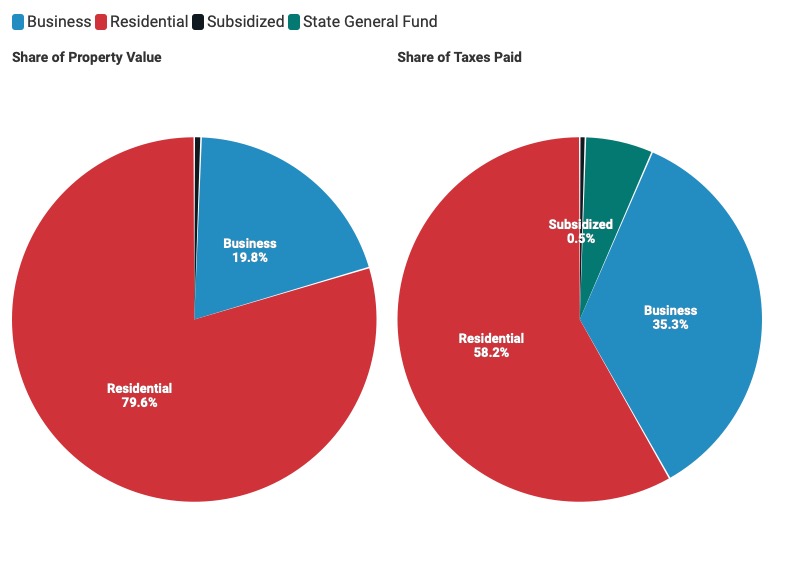

Commercial Property Taxpayers Face a Disproportionate Tax Burden in Arizona

- Business taxpayers make up less than 20% of property value, but pay over 35% of the taxes

- Despite being 80% of the property base, residential payers – including commercial operations treated as residential by the property tax code, like childcare centers – only pay 58% of the taxes.

- The Homeowner’s Rebate sees the State General Fund directly making 6% of all property tax payments to school districts on behalf of homeowners, which distorts incentives and potentially encourages residential property owners to favor higher property tax rates.

- Subsidized commercial taxpayers – like manufacturers located in Foreign Trade Zones or commercial leases on public land – ironically end up paying their ‘fair share’ of taxes net of subsidies, due to generally higher business property taxes

- Taxes on personal property (which are 53% of the total assessed valuation in all subsidized property classes) drive this unintuitive fact.

- Of the $9 billion in statewide property taxes expected to be paid for FY 2022, $868 million will be on business personal property

- When fully phased in after approximately 10 years, this proposal will reduce statewide property taxes by approximately $182 million/year relative to current law.

Arizona’s Disproportionate Tax Structure Gives It Relatively High Business Property Taxes

- Even as the statewide average property tax rate is low, Arizona’s effective business property tax rate (2.26%) is the 6th highest in the United States

- According to the Texas Taxpayers and Research Association, neighboring California – a regional competitor with Arizona – has only a 0.96% effective business property tax rate.

- The average business property tax rate for the United States is 1.45%.

- Capital purchase decisions are driven by return-on-investment (ROI) – if a given purchase will not generate a higher return than viable alternatives, it will not occur

- Personal property taxes directly lower the return-on-investment for a given capital purchase, reducing the equilibrium level of investment within the taxing jurisdiction.

- Since capital is mobile, these taxes also have the effect of increasing investment in competing lower-tax jurisdictions.

- In a hypothetical example of a $100,000 investment in machinery that generates $200,000 in gross revenue over ten years, the present-value ROI increases nearly 14% under HB 2822 relative to current law and reduces lifetime property taxes paid on the equipment 92%.

Personal Property Taxes are Particularly Harmful Relative to their Share of Public Revenue

- Of more than $9 billion in statewide property tax revenues, less than $900 million is attributable to business personal property

- Although personal property makes up between 25% and 50% of real property values, the combination of existing accelerated depreciation schedules and exemptions reduces its share of taxable value to less than 10%.

- However, the tax is not fixed or proportionate – as a business grows and invests in more capital equipment (desks, computers, machinery) its tax liabilities increase faster than revenue.

- Further, quirks in the existing depreciation schedules mean most property increases in taxable value over its first five years of life, even as the book value of the asset falls.

- Accounting and compliance costs are significantly higher for personal property – a business must track both purchase value, and depreciated taxable value of an asset across its life, and use separate valuations for tax recordkeeping versus financial recordkeeping.

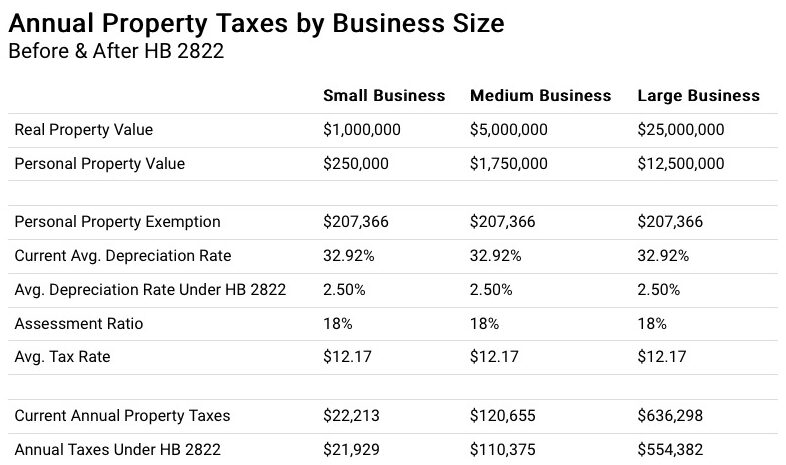

- HB 2822 addresses both problems by applying a consistent and low valuation factor (2.50%) to the asset across its life – dramatically simplifying compliance while minimizing the overall tax burden.

- By encouraging new investment and targeting business activity broadly – with a particular benefit to business activity with high intermediate and capital costs – the policy change can be expected to generate substantial economic benefits

- CSI estimates that HB 2822 will save commercial taxpayers an average of at least $60 million/year over the next 10 years (average annual savings net of potential offsetting tax increases), and by 2032 results in savings of up to $223 million/year; these savings could be offset by some combination of property tax increases and reduced state and local government spending.

- Lower relative costs of capital should result in increased capital-intensive investment by producers in Arizona; this investment, in turn, should generate returns to employment, Gross State Product, and state and local tax revenues which at least partially offset the costs of the tax reduction.

- We used the Regional Economic Model, Inc. (REMI) – a dynamic input-output model – to measure the changes in producer behaviors and Arizona’s general economy from a combination of:

- Reductions in the cost of capital for businesses that, as best we can tell given the aggregation of data in the model, are probably not centrally valued (and therefore subject to the policy change) and in proportion to those businesses share of total State intermediate demand (so that more capital-intensive businesses were more highly impacted than their relative share of Gross State Product might otherwise imply).

- Increases in property tax collections, relative to a baseline wherein the appreciation of personal property (as assessed by taxing jurisdictions) was otherwise available to facilitate minor reductions in statewide property tax rates via Arizona’s Truth-in-Taxation statutes.

- Reductions in Local government spending, relative to a baseline wherein taxing jurisdictions have perfectly balanced budget constraints and must fully offset foregone future revenues from business personal property taxes with spending cuts.

- Reductions in State government spending, relative to a baseline wherein taxing jurisdictions have perfectly balanced budget constraints and must fully offset foregone future revenues from business personal property taxes with spending cuts.

- Overall, we find that this policy induces positive net economic effects in Arizona across all sectors except net government spending, even under the most implausible scenario wherein all taxpayer savings are recaptured through a combination of other property tax increases and state & local spending reductions.

- We believe the most plausible outcome of this policy is effective state and local government spending neutrality, with the net costs of the capital tax reduction absorbed through a combination of other property tax increases and reductions in cash reserves, relative to the baseline scenario – or Scenario 2 in the summary table on page 5 of this document.

© 2022 Common Sense Institute